What is a Christian?

In a preface to his book: Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis highlighted a trouble that he had with the term, "Christian". Is a 'Christian' any person who identifies himself as a Christian? Or perhaps, it is a person who has responded to an 'alter call' and has 'walked down the aisle', and said the 'sinner's prayer'? After all, the New Testament itself requires an 'open confession' of Christ.

Yet, Scripture nowhere teaches that it is by a 'confession' that anyone becomes a Christian. And we know that many who respond to a public invitation from the pulpit never, in reality, become Christians.[0]

Lewis was worried that the term, 'Christian', was steadily losing its meaning. And consequently, he adopted, for the purpose of his book, a definition which he thought would be useful: A Christian is a person who accepts the core doctrines of Christianity: Creation, The Fall, Redemption, and Restoration. In his own words:

Is it any person who mentally accepts the Christian doctrines to be true?

To be clear, I love C.S. Lewis. But such a definition runs into some problems and might mislead unsuspecting readers. In his book, The Abolition of Man, Lewis chides two english school-teachers, Gaius and Titius (not their real names), for carelessly ingraining false philosophical assumptions into the minds of the young students of a school. He writes:

In defining Christianity as above, Lewis has done precisely the thing for which he chided Gaius and Titius. According to him, his definition was not intended to be theological or moral, but aimed at being "useful", and "clear". But the definition that Lewis proceeds to give, in fact, does introduce into the minds of his readers an assumption which is certainly very theological and moral in nature: that the essence of a Christian is in a mental or intellectual acceptance of doctrines.

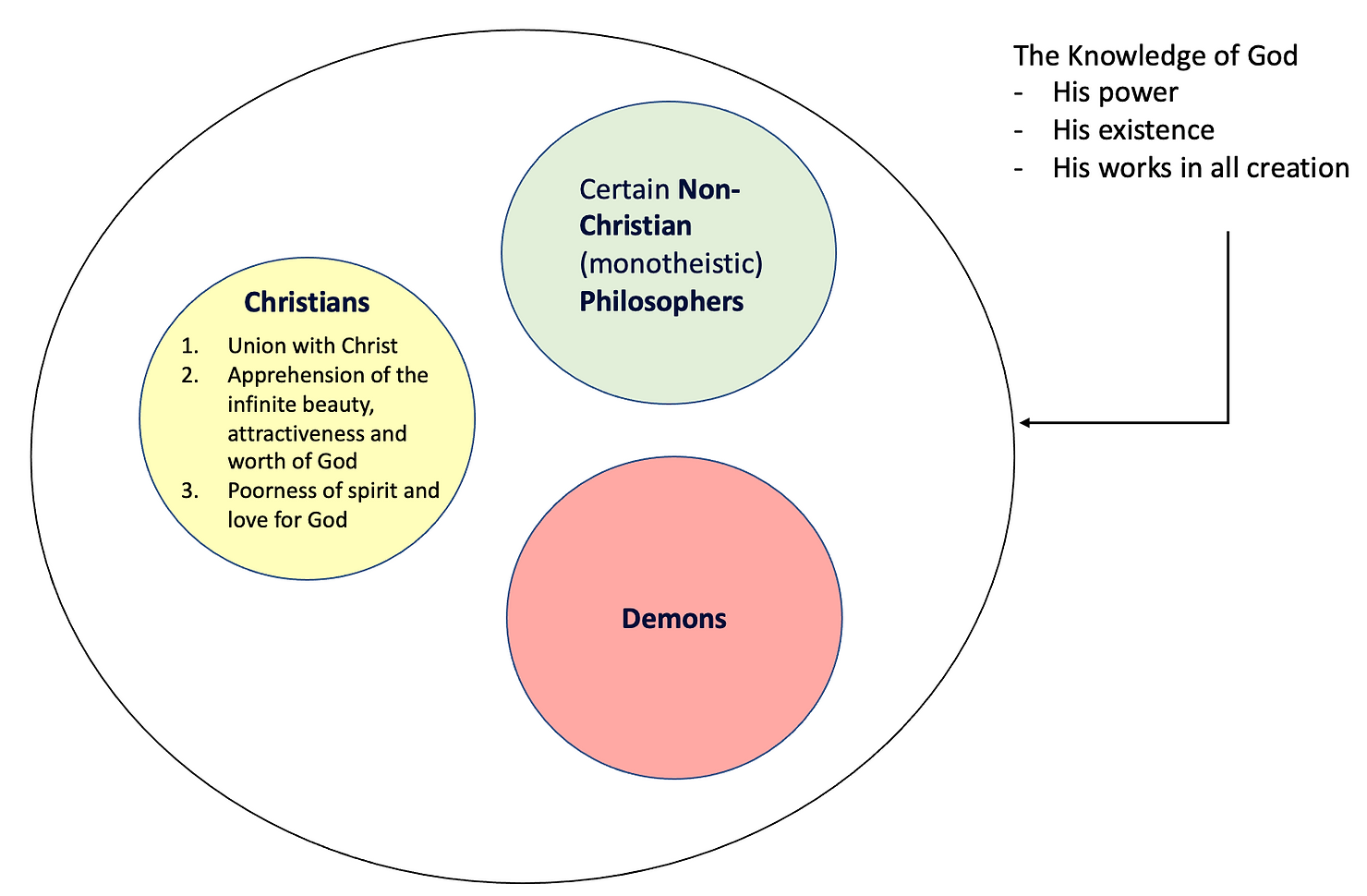

The Apostle James, however, points out the problem with that. "You believe that God is one", he says, "You do well. Even the demons believe - and shudder!" (James 2:19). In this verse, we see that mental assent was one of the things that some people depended on as evidence for their "good estate" with God.[3] In those days, the great doctrine of the existence of only one God was a visible and noted distinction between professing Christians and the heathens.[4] Therefore, many trusted in this as the evidence that they had secured the great and eternal privileges (such as eternal life). But the Apostle James here denies that this is any evidence of a person's state of salvation, because the devils have such knowledge too. But the devils are as far from being christians as heaven is from hell. Thus, we infer the principle that no speculative knowledge of the things of Christianity is any certain sign of saving grace.

Before his fall, Satan was one of the angels who continually beheld the face of the Father in heaven. He has great knowledge of heaven, for he was once an inhabitant of it. Similarly he has great knowledge of hell, and the nature of its misery, for he is the first inhabitant of hell. He was a spectator of the creation of the visible world, and continues to spectate how God governs the world in all ages, from generation to generation. Being in great opposition to God, he carefully observes all of God's works so as to make warfare against them. No doubt, he must have a great degree of knowledge concerning Jesus Christ as the Saviour of men, and the nature and method of the work of redemption. He also has a great knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, for he made use of the words of Scripture in his temptation of our Saviour in the desert. Therefore, whatever clear notions a person may have of the attributes of God, the doctrine of the Trinity, the nature of the two covenants, or on the offices of Christ and the way of salvation by Him - that is no certain evidence of any degree of saving grace in his heart.[5]

In saying this, we do not mean to say that the knowledge of God is unimportant. On the contrary, the content of the Christian faith lies squarely in knowledge of truth, which leads towards godliness.[6] In fact, it is precisely the decline in the knowledge of God that constitutes the bulk of the problems of the today's churches (and which forms the impetus for the founding of reformed.asia). The principle we intend to convey is not that divine knowledge is nonessential, but that true Christianity goes beyond the mental assent of doctrine. The Holy Spirit is poured out not just so that we can come to know the works of God, but so that, in knowing them, we may "glory in them", and thank and praise God for them; and that we may fear and worship God on account of them, consecrating both our minds and hearts to the honour of His name.[7]

Further, while Scripture often speaks of the possession of divine knowledge as a hallmark of Christians, it has in view something other than a pure intellectual exercise. John 17:3 states: "And this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent". Psalm 9:10 states: "And those who know your name put their trust in you, for you, O Lord, have not forsaken those who seek you." And Philippians 3:8 states: "Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord". But the type of knowledge here professed is fundamentally different from the type of knowledge possessed by the demons. In these verses, the knowing of God, or of the name of God, or of Christ, is not simply a mental assent or intellectual acceptance, but goes beyond that and includes a wholehearted worship and adoration of the Creator. The Anti-Christ on the other hand, opposes God notwithstanding his knowledge of Him. Why the difference?

One might suggest that the reason for this difference in the responses towards the heavenly Father is because at their respective roots, Christians are good while the devil is evil by nature. But that would not be true. Paul writes in Romans 3 that "all, both Jews and Greeks, are under sin, as it is written: "None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one... There is no fear of God before their eyes." And again, he writes in Ephesians 2, to his Christian brothers and sisters, saying: "And you were dead in the trespasses and sins in which you once walked, following the course of this world, following the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience - among whom we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind". Indeed, because of the sin of Adam, we are, as David says, "brought forth in iniquity" from the time of our conception (Ps. 51).

Rather, a Christian is any person who is in Christ

Instead, the correct answer lies in how the New Testament thinks about Christians. The New Testament overwhelmingly refers to believers as those who are "ἐν Χριστῷ" - that is, those who are "in Christ", or "in union with Christ". The expression, in one form or another, occurs well over one hundred times in Paul's thirteen letters.[8] It is only those who are in Christ that appropriate the benefits which all flow directly from that union (such as Justification, Sanctification, Reconciliation, Adoption and so on). And out of all the benefits, it is only in sanctification that we begin to see the external and visible effects of the believer's union with Christ (such as a growth in personal holiness; the conformity to the law of God; love for Christ; obedience to Christ; love for the body of Christ; a delight in the character of God, a sense of sweetness at the Law of God; poorness in spirit; amongst others). It is by such attributes that we may outwardly recognise a Christian, but all these attributes would not exist if not for the believer's union with Christ. Hence, the essence of a Christian lies in his invisible and internal spirit-initiated union with Christ, and not the outward profession of his religion.

This then, is what makes Christians different from the reprobate, the demons, and Satan himself: our union with Christ, wrought by the Holy Spirit. It is because of this union that we respond to the knowledge of God and of the Gospel, obtained through God's use of preaching and preachers, in faith, repentance, and worship (rather than with hatred and the rejection-of-truth).

But because such a working of the Spirit in uniting the Christian with Christ is invisible to the human eye, The church has relied on external and observable signs, attributes, and actions to recognise fellow members of the body of Christ. The confession of faith and the profession of assent to the fundamental doctrines of Christianity thus serve as suitable thresholds for this task, for man does not see as the LORD sees: "man looks on the outward appearance, but the LORD looks on the heart" (1 Sam 16:7). Yet, we must not confuse external evidences with the internal reality. If the essence of a Christian is indeed an inward union with Christ, we may not rely on the mental assent of the Christian God or the outward profession of it, or any works of our hands, or anything else in all creation as the basis of our confidence in appropriating eternal life. No - our confidence must rest only in the person of Christ for justification, sanctification and eternal life. The Gospel is Christ himself, clothed in its garments. And so the bedrock on which a Christian stands is none other than the goodness, graciousness, faithfulness, steadfastness, and loving kindness of our Father, in giving us Christ Jesus our Saviour, in whom we are.

Assurance of Christ and Assurance of Salvation

Of course, the degree of certainty with which we know that we are in Christ will be affected by the strength of the evidence of that union. As Ferguson puts it, "high degrees of Christian assurance are simply not compatible with low levels of obedience, If Christ is not actually saving us, producing in us the obedience of faith in our struggle against the world, the flesh and the Devil, then our confidence that he is our Saviour is bound to be undermined. This is why there is a strong link in the New Testament between faithfulness in the Christian walk and the enjoyment of assurance. Obedience strengthens faith and confirms it to us because it is always marked by what Paul calls, "the obedience of faith"".[9] Accordingly, when we search ourselves, and find traces of holiness, repentance, faith, the fear of God, and love of Christ, we must not abstract these benefits from the person of Christ, with whom we are in union with, and imagine that we possessed these benefits in ourselves. Instead, we should praise God who has, on account of His own good pleasure and not becuase of any degree of faith or repentance within us (for we had none), given us the Christ. Accordingly, it is in Christ that we come to obtain the above benefits which we rejoice in. Likewise, if we, upon searching ourselves, see no trace of conformity to the Word of God, we must not despair, for it is not on the basis of our conformity to the Law that he gives us Christ. On the contrary, the invitation of our gracious Saviour still stands:

- Isaiah 55:1-2

A temptation to work to forcefully produce the evidence of faith

In his first epistle, the Apostle John writes, at least in part, to assure believers: "I write these things to you who believe in the name of the Son of God that you may know that you have eternal life" (1 John 5:13). So he writes:

"We know that we have come to know him, if we keep his commandments. Whoever says 'I know him' but does not keep his commandments is a liar, and the truth is not in him" (1 John 2:3-4).

"Everyone who believes that Jesus is the Christ has been born of God, and everyone who loves the Father loves whoever has been born of him. By this we know that we love the children of God, when we love God and obey his commandments. For this is the love of God, that we keep his commandments" (1 John 5:1-3).

"If you know that he [ie, Christ] is righteous, you may be sure that everyone who practices righteousness has been born of him" (1 John 2:29).

"We know that everyone who has been born of God does not keep on sinning" (1 John 5:18).

"We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers" (1 John 3:14).

"Thus whoever loves [ie, in the sense previously defined] has been born of God and knows God" (1 John 4:7).

As put by Ferguson, "Faith works by love; and love expresses itself in obedience. Therefore, the "obedience of faith" attests the reality of faith".[10] But upon reading the above, many of us might be tempted to force ourselves to obey God's commands to be righteous and to love Him and the brethren, for the sole sake of building in ourselves a "faith" that God's promises apply to us, and to gain an assurance that we are of God. But if we do so, such a faith will not be a faith in the free gift of Christ. Instead, it is a useless, treacherous, self-deceiving faith in our own works. The evidence of faith cannot be artificially manufactured from works. The evidence of faith can only be produced by faith, which comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ (Rom. 10:17).

That is why we must resist that temptation, and fly straight to the cross, where we meet the full benevolence of God in giving us union with Christ. It is from this union alone that we may obtain faith, and consequently, love and obedience, which confirms our inheritance of eternal life. In his writing of the verses above, the Apostle John is neither saying that we must kill sin so that we can ensure our faith is real, nor that we must constrain ourselves to be more righteous in order to gain the assurance of salvation. Doing so would be to skip the crucial exercise of faith in Christ. Instead, he lovingly writes to give believers some markers, through which, in the context of faith, they can confirm their union with Christ.

For more on the topic of assurance, there is a free ebook by Spurgeon, available here.

[0] Iain H. Murray, Evangelicalism Divided: A Record of Crucial Change in the Years 1950 to 2000 (The Banner of Truth Trust, 2000), at p 53.

[1] C.S. Lewis, Preface to Mere Christianity (The Complete C.S. Lewis Signature Classics, HarperCollins Publishers, 2002), at p 10.

[2] C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (Samizdat University Press, 2014, at Chapter 1.

[3] Jonathan Edwards, True Grace Distinguished From The Experience of Devils (The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Vol 2, The Banner of Truth Trust, 1834), at p 41.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid. In this paragraph and the paragraph above, I have quoted some of Edward's sentences verbatim.

[6] Herman Bavinck, The Wonderful Works of God: Instruction in the Christian Religion according to the Reformed Confession (Westminster Seminary Press, 2019), at p xxxi.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Sinclair B. Ferguson, The Whole Christ: Legalism, Antinomianism, and Gospel Assurance - Why the Marrow Controversy Still Matters (Crossway, 2016), at p 45.

[9] Id, at p 201.

[10] Id, at p 202. The verses from 1 John have also been extracted from this text.